The Beginnings of Agriculture in Washington State

|

| A Man In the Field With His Team and Plow, ca. 1910 † |

Commercial agriculture in Washington State can be traced back to the Hudson Bay Company’s establishment of Fort Vancouver in 1824. To meet the North American director’s insistence that the company be self-sufficient, Fort Vancouver raised livestock, cultivated land, and planted orchards to supply food for the fort and for other HBC fur-trading posts. As Washington’s white settler population increased, so did the number of farms. In 1860 there were 1,330 farms, almost all in western Washington. (Washington State Dept. of Agriculture [1989], 23)

By 1890 the number of farms increased to 18,056, and Eastern Washington was increasingly becoming the center of farming in Washington. Western Washington farms averaged 120 to 150 acres and focused on potatoes, hops, market garden produce, and milk. In contrast, eastern Washington farms were larger, averaging almost 300 acres. Cattle and sheep grazed on open ranges but wheat emerged as the dominant crop. (Washington State Dept. of Agriculture [1989], 23-24)

Railroads and Irrigation Impact Agriculture

With the construction of railroads, agriculture expanded beyond the Walla Walla region in Eastern Washington as farmers were able to transport their grain to market. By the mid-1880s, the Palouse and Walla Walla Valley produced 7.5 million bushels of wheat per year. By 1910, wheat represented 44.5 percent of the value of all Washington crops (Schwantes 1996, 206) and flour milling ranked second only to lumbering among Washington’s industrial enterprises. (Ficken and LeWarne 1988, 61)

Irrigation transformed, expanded, and diversified Washington agriculture. The federal government greatly improved irrigation farming by providing technical, financial, and educational assistance. The United States Reclamation Service launched the Okanogan, Wapato, and Tieton irrigation projects and expanded the private Sunnydale initiative through the National Reclamation Act of 1902. The resulting irrigated land was the most expensive farmland in Washington and farmers could only afford to buy and cultivate small tracts of land. Farmers near Yakima, Wenatchee, Chelan and Okanogan, thus, turned to apples over wheat, a crop that enabled substantial profits from small orchards. (Gates 1948, 223; Ficken and LeWarne 1988, 66) During a period known as "apple fever" in 1908, Washington planted at least one million apple trees, quickly becoming the leading producer of apples in the nation by 1917. (Schwantes 1996, 211)

Post-War Economic Developments Impact Farmers

|

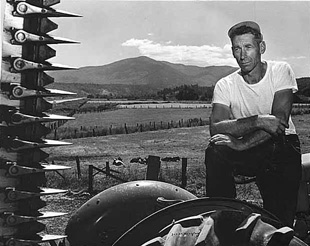

| Dairy farmer Elvin (Al) Barlow, Issaquah, 1953 • |

World War I brought prosperity to Washington farmers, many of whom expanded their acreage and purchased equipment. Peace, however, reduced agricultural prices, farm incomes, and ultimately, land values. In response, farmers increasingly turned to specialty crops and cooperative organizations to market their products. Producer organizations were established for wheat, fruit, poultry, and dairy products that provided storage, standard grades and varieties, packaging and processing techniques, and wider distribution systems. Agricultural experiment stations also lent guidance through education and technical programs and publications. Despite all these fluctuations and changes, more than two thirds of agricultural income still came from wheat and apples in 1930. (Gates 1948, 224-227)

Postwar economic changes deeply affected irrigation projects. The total acreage of irrigated land declined by 30,000 acres during the 1920s. Since the cost of preparing land for irrigation was the highest in the United States, intensive rather than extensive irrigation came to define Washington agriculture. With unexpected public funding, both the Grand Coulee and Bonneville dam projects began construction in 1933-34 as part of the New Deal. The Columbia River and Columbia River Basin would change radically as a result, with the dams promising the irrigation of more than a million acres of arid land. (Gates 1948, 227-228)

References

Ficken, Robert E., and Charles P. LeWarne. 1988. Washington: A Centennial History Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Gates, Charles M. 1948. A Historical Sketch of the Economic Development of Washington since Statehood. Pacific Northwest Quarterly 39: 214-232.

Schwantes, Carlos A. 1996. The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Washington State Department of Agriculture. [1989]. Washington's Centennial Farms: Yesterday and Today. Olympia, Wash.: Washington State Dept. of Agriculture.

Bibliographies

Agriculture Books, 1820-1945 (pdf)

Agriculture Journals, 1820-1945 (pdf)

Agriculture Theses, 1820-1945 (pdf)

Agriculture titles filmed by the project (pdf)

†Negative Number: 35-37-07. From the Frank S. Matsura Collection, WSU Libraries Digital Collections.

•Image Number: 1993.20.76. From the Josef Scaylea Collection, MOHAI.