Camp Life

Camp Cooks

|

|

|

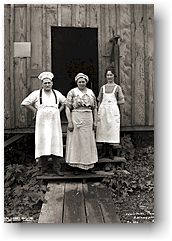

Mess hall crew, Lewis Mills and Timber Co., ca. 1922. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 1740 |

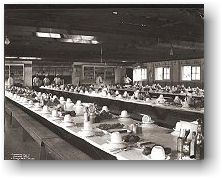

Cooks in logging camps were extremely important to the success of the operation. A cook who could provide good, hearty meals to loggers kept the crews happy and contributed to the success of the company. A bad cook could cause discontent among the men and cause them to quit and move on to a better run camp. The loggers ate enormous quantities of food, an average of 8,000 calories a day, in order to have the stamina for the work of one 10-hour shift. Riggingmen, fallers, and buckers are said to have expended 8 to 12 calories per minute, with heavy gear and foul weather adding to the caloric burn. The cook arose at 3:30 or 4:00 in the morning and had breakfast ready before 6:00. The call to meals was a blast on a cow’s horn, beating on an iron triangle or a gong made from a circular saw blade. No talking was allowed at meals, other than to ask for food to be passed, and most meals were consumed within 12 minutes. A good logging camp cook could routinely produce meals that compared favorably with those served in the finest hotels. A survey of logging camps in the Northwest in the 1930s found the following items frequently served: corned beef, ham, bacon, pork, roast beef, chops, steaks, hamburger, chicken, oysters, cold cuts, potatoes, barley, macaroni, boiled oats, sauerkraut, fresh and canned fruits, berries, jellies and jams, pickles, carrots, turnips, biscuits, breads, pies, cakes, doughnuts, puddings, custards, condensed or fresh milk, coffee and tea. Breakfast and dinner were served in the cookhouse.

|

|

|

Mess hall interior, Greenwood Logging Co., ca. 1930. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 1407 |

Waiters, waitresses, or “flunkies,” usually women, fired the wood stoves, did prep work for the cook, waited tables, and handled the cleanup. There were a few women cooks in the camps as well. As the men went off to work in the woods, they picked up a lunch bucket that the cook or flunkies had packed for each of them, usually consisting of items such as meat sandwiches, boiled eggs, fresh fruit, and a dessert of pie, cake or doughnuts.

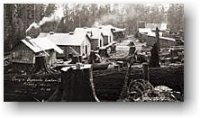

Bunkhouses

In the early 1900s, logging operations began building logging camps at the work site. In 1908, the Whitney Camp on the Columbia River near Astoria, Oregon, boasted hot showers, a library, electric lights, refrigeration, a barbershop, and beds with springs and mattresses. But conditions in most camps were less than comfortable. A few companies housed their men on trains equipped with dining and sleeping cars. Most companies, however, opted to build bunkhouses on skids, so that the entire operation could be loaded onto rail cars and shipped to new work sites once workers logged out an area. Bunkhouses, typically 10 by 24 feet, housed as many as 16 men in two-tiered, wooden bunks that lined the outer walls. Loggers had to supply their own bedrolls. Kerosene lamps provided dim light, and a pot-bellied, cast-iron stove in the middle of the room provided heat and a handy place to dry clothes. Lice and bugs were a frequent problem in bunkhouses.

Recreation

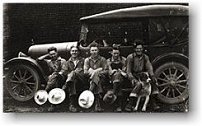

Daylight permitting, the logger’s workday lasted 10 or 11 hours, Monday through Saturday. The little time that remained for recreation was cherished by the workers. Playing cards was a favorite evening pastime – often cribbage during the week and serious poker on Saturday nights. If it was possible to get to a nearby town with a bar, loggers spent Saturday nights and holidays on booze, women and spending their paychecks. Many loggers owned a suit of clothes for trips to town. Tailors often visited camps to display cloth and take measurements, bringing whiskey with them as a courtesy to their customers. Missionaries also visited the logging camps on occasion.

|

|

|

|

|

Logging camp, Wynooche Timber Co., ca. 1921. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 5191 |

Mill workers sitting on running board of a car, probably Pe Ell, ca. 1920. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 1407 |

Family group, Manley-Moore Lumber Co., ca. 1927. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 1973 |

Families

Accommodations for families were limited in logging camps. Families lived in small shacks provided by the lumber company, and children were often educated in one-room schools set up at the camp. Because the families moved frequently and lived in isolated places, children rarely made lasting friendships or attended schools in town until they reached high school.

Asian Crews

|

|

|

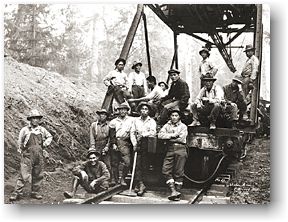

Asian track gang, Schafer Brothers Logging Co., n.d. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 3795 |

Workers from Japan, China, the Philippines and other Asian countries often worked in the logging camps and sawmills. In the logging camps, they usually constructed and maintained the logging railroad tracks. In the sawmills, Asian workers were usually assigned to work the “green line” (an area of sawmill where freshly milled lumber is pulled from the conveyors and stacked) and at the millpond, two dangerous and low-paying work areas. Asian workers had separate housing, either bunkhouses or family housing.

“The Chinese made up the railroad maintainance crew. The section men, they had their own cookhouse and bunkhouse in camp – they were honest and clean, wonderful people. Everybody thought the world of them. On the Chinese New Year, they always invited the train crew to an eight course Chinese dinner with a bottle of beer for every guest and a bottle of scotch for every three guests.” [Source: “Waddy” Weeks quoted in Logging As it Was by Wilmer Gold (Victoria, B.C.: Morriss Publishing, 1985.)]

Continue to next section, "Civilian Conservation Corps"