Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Company

|

|

|

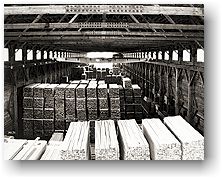

Interior of lumber shed, Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Co., n.d. Special Collections, UW Libraries, C. Kinsey 4171 |

In the early 1890s, the town of North Bend was called Snoqualmie, and the town of Snoqualmie was called Snoqualmie Falls. What is now Snoqualmie got its name - and the railway depot that was originally slated to go to North Bend - by wooing railway officials when North Bend's founder (land speculator Will Taylor, who platted the city) was out of town. To avoid confusion, railroad officials created rules against nearby towns sharing similar names and so "forced (what is now) North Bend to change its name and made Snoqualmie Falls drop "Falls" from the town's name. The railroad depot, on Railroad Avenue in Snoqualmie's old downtown core, soon attracted other business interests to the city. Edmund and Louisa Kinsey, who are believed to have purchased the first lots in the new town, quickly became community stalwarts.

Newcomers flooded into Snoqualmie after an underground power plant was built at Snoqualmie Falls in the late 1890s, producing electricity and local jobs. A small company town, including a railroad depot, grew up around the falls. A second powerhouse was added in 1911. A few years later, in 1917, Snoqualmie Falls Lumber cut its first log. The owners of the second all-electric lumber mill in the country built their own company town - called Snoqualmie Falls - across the river and up a hill from Snoqualmie. At its peak, the mill town included 250 homes, a hotel, community center, 50-bed hospital, barber shop, grade school, boarding house for single men and eight bunkhouses built for Japanese workers. During World War I, soldiers were assigned to the mill and woods so that wood, an essential material for the war effort, could still be logged and processed.

Though mill wages fell during the Great Depression, Snoqualmie Falls Lumber - which later became Weyerhaeuser - survived the hard times to enjoy the nation's post-World War II building boom that increased demand for lumber. By the 1950s, the idea of a mill town had fallen out of vogue. The houses at Snoqualmie Falls were in need of expensive maintenance, and mill workers, who rented from the company, wanted the chance to own their own homes. Many of the houses were moved across a temporary bridge on the Snoqualmie River to create the Williams Addition to Snoqualmie in 1958. By 1960, Snoqualmie's population had stabilized at around 1,200 residents. By then, agriculture was no longer a major economic force in the community, but Weyerhaeuser's mill operations were still a mainstay. With the completion of Interstate 90 in the 1970s, more Snoqualmie residents began commuting to jobs outside the city. Still, over the next 30 years, only about 11 people were added to the city's rolls each year. In 1989, Weyerhaeuser closed its main mill above Snoqualmie. In 2002, the company announced it was shutting down its Snoqualmie dry kilns and planing plant. The closure, along with Weyerhaeuser's decision to mothball its White River mill in Enumclaw, effectively ended the company's 100-year logging operation in King County. [Source: Green, Sarah Jean. "Snoqualmie's prairie roots: A town grows from backwater to economic center." The Seattle Times, Friday, December 20, 2002]

Continue to next section, "Logging Operations & Locomotives"